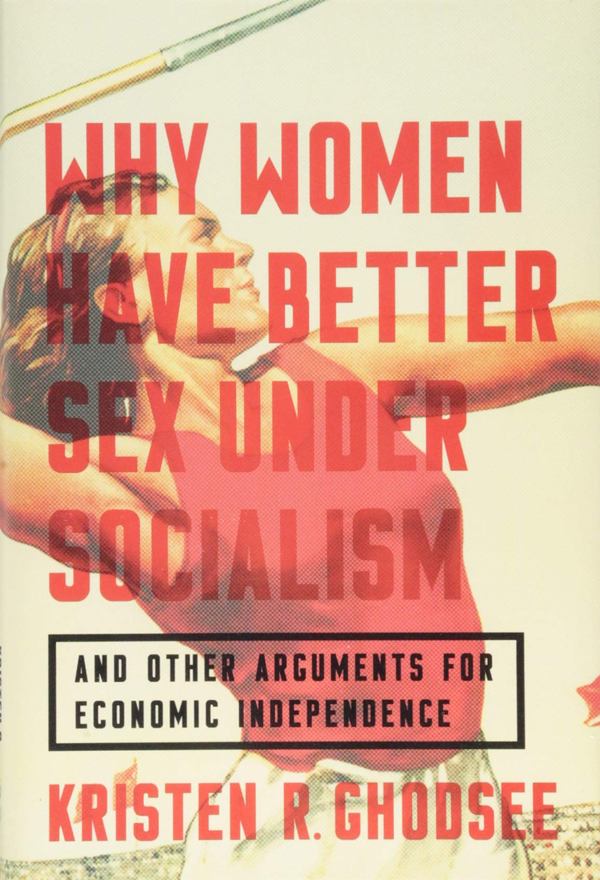

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: and other arguments for economic independence

Kristen Ghodsee is an anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania whose scholarly work focuses on Eastern Europe. In 2018 she published an important book, essentially advocating for democratic socialism and illuminating the ways in which the state should intervene in the market in order to achieve the full emancipation of women. She is trying to show what happens when women are no longer economically dependent on men.

The main argument of the book goes like this: Unregulated capitalism is bad for women, but if we adopt some ideas from socialism, women can have better lives. If done properly, socialism can lead to economic independence, better labor conditions, better work/family balance, and yes, even better sex. According to Ghodsee, personal satisfaction in the bedroom resulted from “socialist lives”.

It is all about social safety nets and creating an environment in which women will not be punished and discriminated against for having children.

Ghodsee urges us to learn from the mistakes of the past, and in order to that, she is suggesting a closer look at the policy practices developed in Eastern Europe during the socialist period. Socialism needs to be released from its historical baggage and therefore “decoupled from the widespread association with forced collectivization, labor camps and purges, just as contemporary ideals of the free market have been disentangled from its past associations with slavery and colonialism”.

Women’s emancipation was crucial in the building of the new post-WWII Eastern European states. Socialist governments made a huge effort to support women’s full incorporation into the labor force. Overturning the widespread perception of women’s comparative inferiority as workers, due to their capacity for child bearing, was not an easy task. Despite important differences between them, these countries devoted vast resources to invest in women’s education and training and to promote them in those professions previously dominated by men. In 2018 there was an article published in Financial Times in which it was revealed that eight out of the top ten countries with the highest rates of women in the tech sector were in Eastern Europe, which is a legacy of the socialist period. A particular normative framework was established which contributed to the emancipation of women, which, among other things, included the expansion of public services. They tried to socialize domestic work and childcare by establishing a network of public facilities; job protected maternity leave was introduced as well as child benefits, which allowed women to find a certain work/family balance.

One of the ways in which socialist countries attempted to counter discrimination against women was by expanding opportunities for public sector employment.

In general, socialist countries managed to reduce women’s economic dependence on men by making men and women equal recipients of services provided by the state. With an independent source of income and state guaranteed social security, there was no economic reason for women to stay in an unhealthy relationship.

Then, 1989 happened. It was a turning point. The collapse of state socialism in Eastern Europe triggered tectonic changes in the region, followed by the absolute domination of neoliberal ideas. The region was turned into a “perfect laboratory” to investigate the effects of (unregulated) capitalism on women’s lives. What was lost? Certainty in a citizen’s life, free education and health care, the absence of fear of unemployment and not having to worry about how to meet one’s basic needs. Unemployment sky rocketed, the long-term process of rolling back the welfare state had started, while the women were forced to go back into the home. Ghodsee successfully demonstrates how free markets quickly eroded women’s potential for economic autonomy. Women became a commodity. Without state funded child care, or well-paid maternity leave, many women were pushed out of the labor market. Most of them now perform care work for free.

This book should become an important teaching text for South African feminist scholars and gender activists. Their main agenda needs to be radically redefined. Preoccupation with identity politics as well as focusing on policies that only benefit a small percentage of middle-class women, should be seriously reconsidered. Even though the glass ceiling needs to be broken, it doesn’t mean that the pressing problems of those nowhere near as high in the reclining order should be marginalized. On the contrary, policies designed to help women get to the top always must be combined with measures to help those women struggling at the bottom.

South African women occupy unfavorable position on the labor market. They participate less in the paid labour market compared to men. Women’s wages are lower than men’s. Women are over-represented in low-skilled and low paid jobs and they are more vulnerable to poverty and social exclusion. Female headed households in South Africa tend to be far worse than male headed households in terms of access to financial assets and access to public assets and services. Oxfam recently published a report stating that South African women are among the most unequally burdened caretakers in Africa. Women spend seven times as many hours as men doing domestic work.

South Africa has one of the highest incidences of domestic violence in the world; and domestic violence is the most common and widespread human rights abuse in South Africa.

New policy instruments are needed in order to address this grim position of South African women, and some of the ideas discussed in Ghodsee’s book offer a way forward.