Think-tank director relates the ‘untold story’ that led to State Capture

The story of State Capture in South Africa goes far deeper than corruption, says Ivor Chipkin, leading scholar and director of the Government and Public Policy think-tank.

The five-chapter report, authored by Chipkin, is telling, because the struggle today is for the very integrity of the state itself, said Thamm. The details of corruption that continue to be revealed at the Zondo Commission indicate that the rules of the political game are defined by the ANC, she said.

Earlier this month, Thamm wrote that the leveraging of taxpayers’ money to fund and hold on to power had become so commonplace that it was now part of the party’s DNA.

“The ANC is in a sense eating up the country. It’s eating up our resources and what is meant for the voter,” she said in the webinar.

Chipkin, one of South Africa’s leading thinkers on government, said he submitted the report to help the commission better distinguish between corruption and State Capture.

While State Capture can be understood as tremendous corruption, the two are not the same, he told Thamm. But the submission of the report also intended to make a political argument: State Capture is not just about corruption.

It goes far deeper and the stakes are high, Chipkin said.

“It is not just a Hollywood story of goodies versus baddies. This is a very complex country with a very complex history trying to come to terms with incredible deep-seated divisions through the resources that are currently available.”

Chipkin said the report was intended to situate State Capture as a historical phenomenon, in relation to how South Africa emerged from colonialism, became a democracy and the massive challenges that came with these transitions.

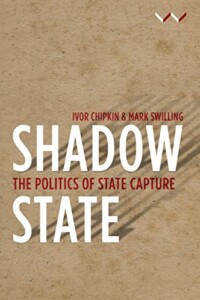

Chipkin was one of the academics who wrote the 2017 report, The Betrayal of the Promise, one of the first studies of State Capture. He co-authored Shadow State: The Politics of State Capture, and founded and directed the Public Affairs Research Institute at Wits University.

“We forget that 20th century South Africa is largely a story of the last 50 years of the National Party deliberately trying to break the state up into a whole lot of different countries,” he said.

“We know the project fails… [but] we often dismiss the homelands and the Bantustans as puppet governments and in doing that, we don’t recognise that by the end of the apartheid era these were substantial entities.”

When the ANC came into power in 1994, the party sought to integrate Bantustan officials and traditional leaders in efforts to stabilise the country, Chipkin said.

The project, allowing homeland officials to gain power over the distribution of senior positions in the public service, is South Africa’s greatest untold story and led to State Capture, Chipkin said.

In the homeland governments, things happened on the basis of personal connection, argued Chipkin.

“That culture enters many of the post-apartheid administrations, especially at provincial and local government level. I think it goes a long way to explain why things don’t happen on the basis of policy or on the basis of regulation and law.

“They happen largely through these very complex, unstable and changing personal networks that people find themselves in.”

Chipkin pointed out that the ANC has never regarded itself as a political party.

“It has always regarded itself as a liberation movement. The ANC doesn’t see itself as representing particular interests and competing with other parties; the ANC has long understood itself as the people itself.”

Now, the ANC needed to start thinking of itself as a political party, Chipkin argued, and the public service had to be professionalised, guaranteeing long-term careers for people.

The current situation could play out in three ways, he said.

The first scenario — a democratic one — is where the elites leave the ANC, resulting in the expansion of South Africa’s political party space.

The second scenario, if the elites stay in the ANC, sees the deepening of contestation.

The third scenario sees the elites taking power through criminality and violence. It was possible that all could happen simultaneously, he said. DM